For the last seven years, I have worked in a community pharmacy that provides distance-care for remote First Nations and Inuit communities in Manitoba and Nunavut. In my practice, I’ve witnessed first-hand how racism, discrimination, and the ongoing effects of colonialism continue to negatively impact health outcomes. This course has allowed me to explore health and health systems more deeply, while also learning more about myself as a healthcare professional. As a result, I’ve developed a deeper understanding that pharmacy practice is about far more than medication expertise. As a profession, we must strive for health equity and adopt a holistic, patient-centred approach to care.

Defining Professional Identity

In order to understand how I can positively impact the healthcare system, I had to first define who I am as a healthcare professional—what my values are, how they shape my practice, and how they contribute to advancing health equity within the system.

The key assignment that significantly clarified my professional identity was the development of an ePortfolio. This project proved to be an invaluable exercise in understanding my role within the healthcare system and the unique contributions I can offer. In addition to greatly improving my computer skills, this experience enabled me to effectively outline and communicate my values, such as health equity and patient-centred care, and how I wish to present myself to colleagues, employers, and patients. This foundational understanding of my role has influenced how I now engage with systemic health issues, interprofessional collaboration, and my work with Indigenous communities.

The social media audit and subsequent development of professional guidelines helped me think critically about how to engage publicly as a healthcare provider. This not only strengthened my ability to build and maintain a professional network, but also ensured that I do so with integrity and respect for my role. Through this exercise, I have further strengthened my ability to build and nurture my professional community, while maintaining a high level of professionalism and integrity in these public forums.

Exploring Holistic and Patient-Centered Definitions of Health

Understanding the concept of health is essential for healthcare providers; what goals do my patients have? Where are the benchmarks for these goals? The definition of health put forth by Krahn et al. (2021), describing it as “…the dynamic balance of physical, mental, social, and existential well-being in adapting to conditions of life and the environment,” offers sufficient flexibility to support a patient-centered approach that evolves with the changing life circumstances of patients.

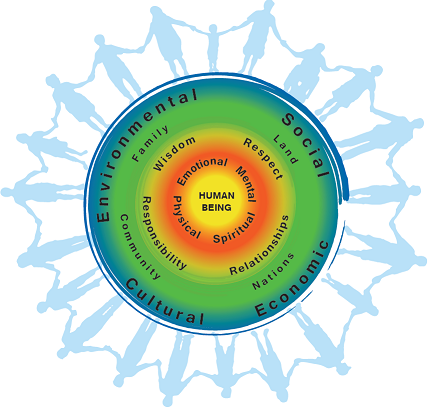

For me, understanding how my patients define health was of equal, if not greater, importance. While I was already familiar with the medicine wheel and its connections to physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual health within a continuum, the First Nations Health Authority (FNHA)’s visual representation of health and wellness (n.d.) significantly expanded my perspective from an Indigenous viewpoint (see figure 1). This representation illustrates the interconnectedness of these essential factors as understood by many First Nations Peoples. Additionally, the similarities to Krahn et al.’s definition serve as a prominent example of the Indigenous concept of Two-Eyed Seeing – viewing the world through both Western and Indigenous worldviews (Wright et al., n.d.).

Figure 1: FNHA’s visual depiction on health and wellness (First Nations Health Authority, n.d.)

As I progress in my role as a healthcare provider, I plan to approach health through these two frameworks while remaining receptive to diverse perspectives, including other cultural frameworks and evolving definitions that reflect the lived experiences of patients.

Determinants of Health & Multilevel Models of Care

Within this course, we examined the social determinants of health, as defined by various organizations including the World Health Organization (n.d.) and the Public Health Agency of Canada (2001). We also explored theoretical models, such as the social-ecological model, as tools to frame our understanding of health and related concepts.

To illustrate my understanding of a multilevel model of care, I analyzed how pharmacists and pharmacy organizations can positively influence smoking cessation across all levels of the social-ecological model (Butler, 2025). This work naturally extends into an exploration of the social determinants of health, as factors like health literacy, social supports, coping ability, and access to services directly impact a person’s ability to quit smoking.

When providing care to Indigenous Peoples, it becomes especially critical to consider the social determinants of health. These determinants are often deeply rooted in broader structural issues, including the ongoing impacts of colonization, socioeconomic disparities, and gaps in healthcare infrastructure in rural and remote Indigenous communities. For instance, in the context of smoking cessation, patients residing in remote areas without access to a pharmacy face significant barriers to obtaining nicotine-replacement therapy and accessing health promotion and healthcare providers compared to those in urban centers. As a pharmacist, this means proactively seeking creative solutions to reduce nicotine use in these populations—whether through community outreach, collaboration with other health professionals, or advocating for better access to cessation tools.

Chronic Disease Prevention & Management

As a pharmacist in a community pharmacy, the majority of my practice focuses on pharmacological management of chronic diseases, particularly for diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and respiratory diseases. However, as I moved throughout this course, examining the definitions of health, determinants of health and multilevel models of health allowed me to reflect on how pharmacists can play a broader role in chronic disease management by considering how patients define their own health, and how social, cultural, and economic factors influence their ability and willingness to manage chronic conditions.

Due to the ongoing impacts of colonization, including food insecurity and systemic barriers to adequate care, Indigenous Peoples are disproportionately affected by type II diabetes (Diabetes Canada, n.d.). Addressing this disparity requires healthcare providers, including pharmacists, to deepen their understanding of trauma-informed care and to actively practice cultural humility. For example, when discussing diet, take into consideration what foods are accessible and culturally appropriate for patients, especially those living in remote communities where the cost of nutritious food is significantly higher (Food Secure Canada, 2016). Ultimately, pharmacists have a responsibility to approach chronic disease management in ways that honour cultural safety, address structural inequities, and recognize the lived realities of their patients.

Interprofessionalism & Future Directions

While traditionally pharmacists have been integral to the dispensing and distribution of medications, their roles are increasingly expanding into clinical settings. As healthcare delivery models shift toward preventive care and interprofessional teams, pharmacists are playing a more central role in patient health management.

Increasingly, pharmacists are shifting their focus towards primary care clinics. In June 2022, the first pharmacy primary care clinic in Canada opened in Lethbridge, AB. Since then dozens of similar clinics have opened in Alberta, Saskatchewan, Ontario, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick (Gysel & Tsuyuki, 2024). Due to the already existing high level of accessibility of pharmacists, these clinics have allowed patients who have struggled to access care elsewhere manage their healthcare needs. These clinics not only improve access to care, but also represent a shift in how pharmacy services are integrated into the broader healthcare system

Alongside the rise of pharmacist-led primary care clinics, many pharmacists are also stepping into roles within interprofessional teams outside of traditional pharmacy settings. A prime example of a collaborative approach is the Nuka System of Care in Alaska, where pharmacists are part of interprofessional teams that provide integrated care (Slaten, 2014). This model is an excellent example of how pharmacists can work alongside other health professionals to address healthcare holistically.

Notably, the Nuka System also exemplifies aspects of self-determined healthcare. While the model was developed by a private organization, it is governed by a board made up entirely of Indigenous customer-owners, and its services are continuously shaped by the feedback and priorities of the communities it serves (Gottlieb, 2013). This approach aligns with the broader movement toward culturally grounded, community-led care models that center patients as partners in their healthcare.

Models like Nuka and pharmacist-led primary care clinics point to a future in which pharmacy practice can meaningfully contribute to health equity, particularly when designed in collaboration with—and for—the communities they aim to serve.

Final Thoughts

As I finish this course, I am profoundly grateful for the opportunity to deepen my understanding of health and the systems that shape it. This experience has strengthened my resolve to work toward a more equitable healthcare system. As I continue through this program, I hope to continue expanding my knowledge of theoretical frameworks, the complexities of healthcare organizations, and where my strengths lie in contributing to a lasting, equitable healthcare system.

References

Leave a comment